Is This the Office of the Future or a $5 Billion Waste of Space?

16 Mar 2016, Lucy Racheva Read the original article…

Workers of a certain age may recall that long ago, people once divided their waking hours into two parts: work and life. At quitting time, Fred Flintstone would slide down the tail of his dinosaur with a “Yabba dabba doo!” That was before technology put the office on vibrate inside everyone’s pocket, and before economic upheaval decoupled work from the security of a full-time job. Today, an estimated one-third of the labor market is made up of “contingent” workers—freelancers, contractors, and the self-employed. When the job is no longer 9-to-5, it’s hard to keep a work-life balance. Now, though, there’s a place where the age-old divide can seem irrelevant, where toil and fun blend together beneath neon signs that say things such as “Embrace the Hustle.” Where there’s always a free keg of beer at the self-serve bar, with a tap that says: WeWork.

At a basic level, WeWork is a company that sublets office space, taking care of many of the time-consuming hassles involved in self-employment. That’s not the factor, though, that has captured the fancy of venture capital investors, who have pushed the five-year-old company’s valuation to a giddy $5 billion. WeWork has cast itself as a new kind of workplace for the post-recession labor force and a generation that has never known a cubicle. It aspires to make your job a place you never want to quit.

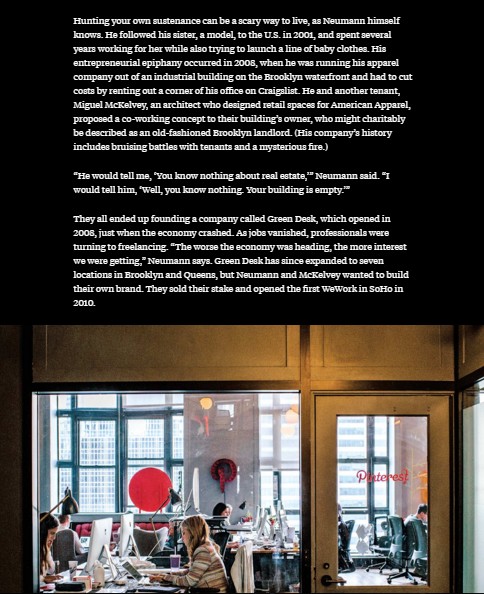

As a freelancer for more than a decade, I was intrigued by this proposition, and in April decided to give WeWork a try. After perusing the options, which start at $45 a month for pay-as-you-go access and run into the thousands for a small office, I sign up for a $350 “unlimited commons” membership. This allows me to use WeWork locations around the world, so long as I can find a seat at the bar. I download the company’s iPhone app and book a spot at a WeWork location on Varick Street in Manhattan. By the next day, I’m tapping away on my laptop in the facility’s second-floor common area. In this WeWork, as in others I later visited, tiny, glassed-in offices line the perimeter. Many have techy names on the doors—Blipit, Znaptag—but there are also lawyers, nonprofits, movie producers, political consultants, and a beef jerky brand. One office is filled with beautiful leather shoes. My work area is lit like a gastropub, with dark wood and leather armchairs, a bar with trompe l’oeil liquor-bottle wallpaper, and microbrews on tap. One afternoon, after a tax-week call with my accountant, I emerge from a phone booth, hidden behind lascivious-looking red velvet curtains, to find a happy hour sponsored by a tequila brand. Soon I’m chatting over grapefruit margaritas with a video game designer who has just joined WeWork, too.

Adam Neumann, WeWork’s Israeli-born co-founder, has called the company a “physical social network,” and it makes every effort to lubricate connections. “We gave 90,000 glasses of beer last month,” he said in a recent onstage interview at TechCrunch Disrupt NY 2015, “which is a number we’re proud of.” Here are some other enviable numbers for WeWork: It currently has 23,000 customers working in 32 locations, about half of them concentrated in New York, where WeWork is the fastest-growing consumer of office space. Flush with $355 million in venture capital from its latest funding round, the company is now expanding internationally, moving into what Neumann calls “high IQ” cities. There are already WeWorks in locales such as San Francisco, Austin, London, and Tel Aviv. Portland, Ore., Toronto, and Berlin are on the horizon. WeWork plans to open three to five new locations a month.

Many traditional real estate investors are perplexed by WeWork’s $5 billion valuation. With that kind of money, you could build the world’s most expensive skyscraper—One World Trade Center, which at 3 million square feet has roughly the same cumulative amount of office space as WeWork—and still have $1 billion left over. And its business model—leasing space wholesale from landlords and then subletting it at a margin in small blocks—is a familiar and fairly risky one. Publicly traded Regus, which dwarfs WeWork with its 2,500 locations in 110 countries, is worth $1.3 billion less by market capitalization. Neumann says doubters don’t grasp the scope of his plans for the workplace. “We are not competing with other co-working spaces,” Neumann says. “We are competing with offices. And that is a $15 trillion asset class in the U.S.”

This article is a derivative work that consists of adaptation or modification of the cited original article. If you have any questions, please contact STONEHARD Ltd.

View original article All news & articles Subscribe to newsletter